“The mind is its own place, and in itself

Can make a Heav’n of Hell, a Hell of Heav’n.”

John Milton, Paradise Lost

[disclaimer: this case is mostly dissected not beyond the scope of primary psychopathy.]

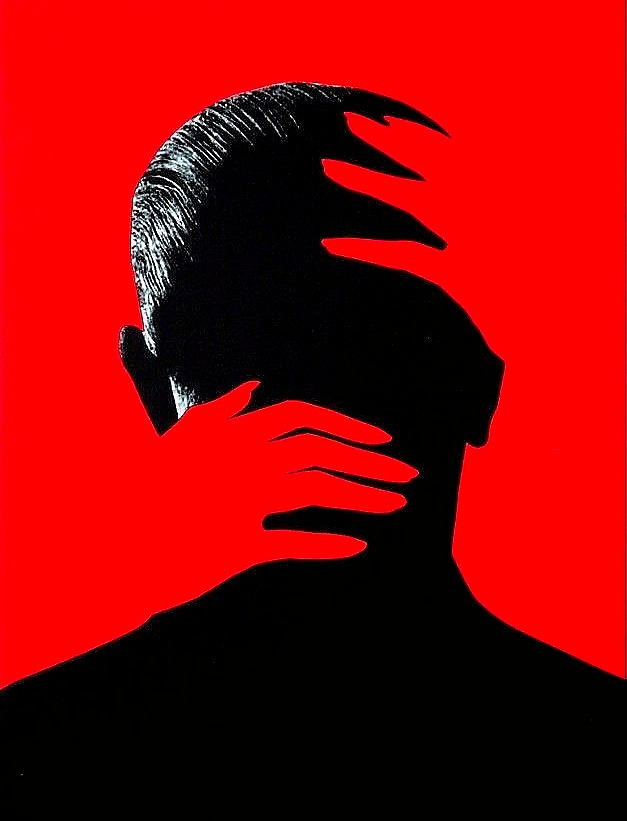

The Superficial Empathizer

Know the words but not the music

When you enter a clinical office, the psychotherapist usually would ask you gently to sit down in some comfy couch with open arms. After that, he or she might proceed to get inside the realm of your affect through the allure of, first, mild questioning—about your current state of mind, mood, or day. It’s relatively no brainer that you can respond readily just until you begin to hesitate to precisely come clean as the questions scale rather piercingly in the coming sessions. This is when you realize something emerging. Nothing but unresolved trauma that has been buried, yet still alive, under the rug of self-deception with which your defense mechanisms are enabled to make their own otherwise narratives.

Understandably, opening up, not to strangers but to oneself alone and just be fully revealing, can be very difficult indeed. You fear you will learn something uncomfortable about yourself. You are forced to sink into a pit of emotional catharsis that alternatively would continue to eat your soul bit by bit at the subconscious level until everything is overwhelming enough it made you seek therapy. While it is true that the job of any clinicians is to bring it to the tip of the client’s mental iceberg (i.e., conscious awareness) and help the client to be able to address it, a well-trained psychotherapist therefore should be ahead of his or her client. Indeed, most well-armed physicians already anticipate a modus operandi in advance to circumvent such obstacles. So with a few technical steps at hands, done with the right prompt and pulled on the right strings, one can get the other person to work in one’s favor and reconfigure from there. And that is what the psychotherapists are professionally trained for, hence skillfully adept to it.

As much psychoanalytical surgery is concerned, this is when a former FBI hostage negotiator Chris Voss, in his book Never Split the Difference, brought out a matter of the so-called “tactical empathy.” It is the ability to label the emotion without actually feeling it. Most people generally like to be listened to what they had to say and have someone else attend to their inner world. It is the feeling when you’re seen and legitimized for whoever you are, is psychologically validating. According to Voss, though emotions are often the roadblock on its own, paradoxically, it is one obstacle that can lead to various directions, for better or worse,—which means that it can potentiate benefits at the opportune moment. Simply put, emotion can be treated as a tool. Therefore, as long as one is able to disarm the resistance of the person talking by means of localizing their affect through simply weaponizing the right words; as their helpless spot is gradually revealing itself, one can thus fuel a set of influence in to this losing void. It is the ability to reverse-engineer their old built-in structure until, eventually, enough getting them change their behaviors. Or, as a behavioral psychologist Carl Rogers encapsulated this technique as the ways in which ‘telling them what you think they think until they think what you said reflects what they said.’

So what’s the catch? Well, it’s important to underscore that the logic of this mental model is one-fits-all. It is inherently neutral given it operates on the ground zero. Devoid of right and wrong. The emphasis “for better or worse” mentioned earlier, might be aiming for separating the wheat from the chaff across this all-encompassing Venn diagram of psychological hacking.

“Powerful people find validation in seeing others change their actions because of them. Power may be used to help or to hurt others, but the goal is to produce an effect.”

—Roy Baumeister, Evil: Inside Human Violence and Cruelty

To the surprise of no one that on the flip side, there are certain individuals who indeed are perfectly capable to leverage this skill as equally good but misused for some despicable ends, if they want to. All meticulously crafted and wittily engineered prior to the victim’s realization of having been deluded along the way. The fact that it lies on a very thin line that picks apart the sides of an angel and of a demon can already blur our focus in profiling psychopathy if not careful. While anyone can be thick-skinned enough to superficially empathize, for the psychopaths, it’s not unique to them to just naturally blend in with both sides.

The Narrative Convincer*

“Relationships develop and mature as people share more and more of their private lives with their partners, including their inner desires, hopes, and dreams. Some of it is personal, other topics are mundane, but all of it is relevant to manufacturing a picture that fulfills, our deep psychological needs and expectations. The psychopath is all too ready and willing to fulfill these needs. Because a psychopath—our new true friend—is an excellent communicator; he or she easily picks out topics that are important to us and reflects sympathetic points of view, sometimes complete with enthusiasm or “emotion” to reinforce the spoken words. The psychopath uses verbal and social skills to build a firm reputation in your mind.”

(Snakes in Suits: When Psychopaths Go to Work, p. 77)

The shape-shifting nature of any confidence game to the absence of the player’s genuineness was even way far from detected until Hervey Cleckley (1903-1984) did—working as a psychiatrist in a psychiatric facility in the late 1930s, once had offenders and patients come to his office as they were believed to be requiring treatment, yet curiously no usual symptoms of mental illness in their display, and in fact they seemed normal under most conditions. He, however, watched them exploit family members and hospital staff by ingratiating with the embodiment of dispositional charm and charisma before the awareness of those victims. To Cleckley’s trained eyes, these individuals were psychopaths.

Hence, as the name suggests, The Mask of Sanity, a classical textbook concerning this particular dark personality, published in 1941. Despite all the odds, Cleckley at that time managed to put his fingers on these individuals who he believed to be suffering from a great deal of emotional poverty. As to help him understand the case, he referred the works of several neurologists before him, like Sir Henry Head (1861-1940), an English neurologist pioneered in the work of somatosensory system and sensory nerves, with the so-called ‘semantic aphasia.’ Here’s how he encapsulated it:

“In semantic aphasia, as described by Head, inner speech or verbal thought is seriously crippled, and the patient usually cannot formulate anything very pertinent or meaningful within his own awareness. He cannot by gestures or verbal approximations hint at his message because he lacks the inner experience on which a message might be formulated... He has no inner production of thought and feeling to transmit. The instrumentalities for language are apparently adequate. They do in fact still perform smoothly but more or less reflexively and apart from inner purpose, manufacturing phrases and sentences but doing so automatically. But the language does not represent or express anything meaningful.”

(The Mask of Sanity: An Attempt to Clarify Some Issues About the So-Called Psychopathic Personality, p. 379)

Essentially, it describes when someone struggles experiencing the depth of meaning behind the expressing words despite the skillful ability of arranging them altogether. Thus, the words lost its value and became hollow. And this is especially the case when the forensic psychologist Robert D. Hare identified it as “glib” to be one of the qualifications in the Factor 1 dichotomy, specifically the interpersonal facet. It is also what partially influenced him to further develop more structured and scalable metrics in measuring psychopathy, divided into two grand dichotomies with two facets in each. He’s probably best known for his Psychopathy Checklist (Hare-PCL), originally published in 1970s. Here’s how he described it more elaborately (with emphasis added):

“[1] For most people, the choice of words is determined by both their dictionary meaning and their emotional connotations. But psychopaths need not be so selective; their words are unencumbered by emotional baggage and can be used in ways that seem odd to the rest of us... [2] It is ‘how’ they string words and sentences together, not ‘what’ they actually say, that suggests abnormality… [3] It’s tangential and somewhat strange, can be interpreted as being evasive or glib.”

(Without Conscience: The Disturbing World of the Psychopaths Among Us, p. 137-140)

This suggests that the bridge between verbal language and emotion can hardly be underestimated in communication, considering semantic processing has the capacity in reconciling this in-between pathway, if not potentiates some transcending human experience. Though aphasia itself has been quite noteworthy in the history of neurology, from which this seemingly counterintuitive phenomenon of speech disorder was precisely what kept many neurologists on their toes. Interestingly, until Cleckley’s groundbreaking finding, psychopathy was never crossed on neither of their minds. However, in the late 1800s there had been a seminal observation—the localization of language function to a specific region of the cerebrum,—popularly attributed to the French neurologist Paul Broca (1824-1880) and the German neurologist Carl Wernicke (1848 – 1905).

In the present days, they’re probably best known for the aphasic condition that each doctor in a separate period of time discovered respectively speech production deficits associated with the posterior part of the left frontal lobe i.e., the inferior frontal gyrus; AND language comprehension impairments in the left temporal lobe i.e., the superior temporal gyrus, which is roughly a decade after Broca published his findings, Wernicke In The Symptom Complex of Aphasia (1874), noted that patients with a lesion of the left temporal lobe had comprehension difficulties but had fluent speech with a relatively intact vocabulary and grammatically correct speech despite incoherent and nonsensical.

Conversely, Broca’s aphasic could grasp the speech but was disfluent in expressing it. Language processing, not only does its neuronal mechanisms operate at the structural levels but also at the functional levels. Putatively, it involves several Brodmann Areas (BA), one for language production i.e., Broca’s area (BA 44 and 45), the other for language comprehension i.e., Wernicke’s area (BA 22). But as general principle, we know that the operating streamline down at the granular level might be more complex and intricate than what clusteringly describes, thereby to know where the glibness trait exactly stems from is not going to be easy to pin down. One we can almost be certain about is that the possible damage to the Wernicke’s area. Also, since Cleckley’s semantic aphasia, a bunch of hypotheses in effort of excavating the psychopath’s brain have so much evolved and been well-documented, tested via a few different techniques of neuroimaging with which a number of experimental studies going in tandem. So that certainly helps reinforce our effort in understanding the psychopatic brain.

“Speech activity, which develops with the mastery of language in a social setting, must rest upon a dynamic system of the greatest complexity involving the simultaneous functioning of various brain areas. Thus the problem of the neurologist, who wishes to study the mechanisms of speech processes, is to determine how these complex functional systems derive from the dynamic structure of the cortex and understand the role of each area in these functional systems; but he must not “localize” these highly complex “functions” in separate isolate areas of the brain. It is easy to see the extent to which this systemic conception of the highly complex forms of nervous activity in man conflicts with the mechanistic type of search for “speech centers”, “writing centers”, or “reading centers”. References to such centers give the appearance of scientific explanation, but actually conceal the path to further analysis of underlying mechanisms."

—Alexandr Luria (1947)

Likewise, it is worth to remind ourselves that whenever we hear the word ‘language’ we can’t orient our thinking only to the extent of verbal transmission in the linguistic and structural sense. We could also sense that the transmission occurs albeit subtle, nuance, abstract, or even implicit, in the ways that certain living organisms (including humans) are capable of communicating what they had to convey to their group however unintelligible,—and still be understood. While psychopaths, too, remain functioning the way they do despite their incapacity of both experiencing aversive or emotionally-laden cues (disgust, threat, distress, etc.) and engaging with someone else’s affect viscerally, it is obvious that emotions be they practiced or expressed are less concrete than they are more abstract. Feelings of sadness, fear, shame, anger, joy, awe, and so on, might be affecting us intangibly non-physical but capable of provoking our physiological response relative to the degree of stimulus.

So as dark personality will be likely to run in continuum given its contribution to the genetic diversity by natural selection that wouldn’t otherwise exist, there should be margin of safety we can understandably tolerate. But this is a discussion for another time.

“Think of Spock in Star Trek. He responds to events that others find arousing, repulsive, or scary with the words ‘interesting’ and ‘fascinating’ [emphases mine]. His response is a cognitive or intellectual appraisal of the situation, without the visceral reactions and emotional coloring that others normally experience. Fortunately for those around him, Spock has “built-in” ethical and moral standards that functions without a strong emotional components that form a necessary part of our conscience.”

(Snakes in Suits, p. 55)

Now, I haven’t been thinking whether Mr. Spock warrants the Hare PCL-R assessment scales neither that I’m aware of whether there has been a paper studying his personality. But it captures the gap quite nicely between the two lateralized brain hemispheres: left and right. It’s akin to inter-hemispheric asymmetry one that is hypo-functioning whereas the other side being hyper-functioning. David Hecht from University College London in his paper (2011) found that psychopaths suffer from this imbalance. He referred to earlier studies concerning the reduction volume of gray matter which occurred in the right frontal and temporal cortices of psychopathic individuals, compared with control subjects. “Across both groups, there was a negative correlation between scores on the affective facets of the psychopathy check list (PCL-R; Hare, 2003) and cortical thickness in the anterior and medial temporal regions, selectively in the RH.” To give a quick background, strictly speaking, temporal and anterior cortices have been partially known for the brain’s emotional regulators that, in this context, are working closely with the frontal cortices—acting as constraint throughout the process of weighing the emotional and cognitive consequences.

Gray matter, meanwhile, is like long-listed points that substantiate the argument presented by the differing regulators ahead of the final ruling or decision—of how to best respond to the given emotional stimulus, including but not limited to, anything that elicits degrees of valence and arousal: odor, emotional tone, facial expression, pictures and words. For instance, studies by Yang et al (2009) found, “Gray matter thinning within the right frontal and temporal cortices, [and] suggest that the structural correlates of psychopathy may be linked to the emotional deficits characterizing psychopaths.” The right hemisphere is functionally involved most in the holistic processing—emotion being one example that is inherently amorphous by default. Both context (manifested through semantic interpretability) and content (manifested through salient attunement) are the components the psychopaths truly struggle to integrate. Their right side running below baseline response makes it so compromised that the neural firing is biased toward the left side. As a result, speech articulation, linguistic eloquence, and grammatical soundness become incommensurate at the expense of its tone, meaning, valence, and salience.

“Words – so innocent and powerless as they are, as standing in a dictionary, how potent for good and evil they become in the hands of one who knows how to combine them.”

—Nathaniel Hawthorne

This hemispheric disintegration deterring the psychopaths from coming into a unified whole, as earlier studies have suggested, might not be limited only to the scrutiny of gray matter’s informational robustness but might have to do with its transmission speed as well,—the white matter. To continue with the previous analogy, if gray matter is the substance of arguments, white matter represents this “architectural” strategy and technique in getting the points across as to whether being efficient or not. If they complement nicely—the communication between differing cortical and sub cortical regions is most likely effective. But functionally they themselves have coexisted more closely than what distinguish them at the structural levels. We learned that gray matter contains white matter strands within. For lest not the informational rush at the crossroads of regional transition zone be off the rail. White matter enables, gray matter executes. Poor communication, impacts outcomes.

Now, imagine there are big themes to be laid out, each distributed to the responsible subsets of brain lobes. These cortices and subcortices involved are clustered together according to the domain they’ve been part and parcel to compute, regulate and represent, through a single “presentation.” Domains such as arousal (thalamus, cerebral cortex), spatial attention (the right side of: parietal lobe, prefrontal cortex, cingulate gyrus), memory (hippocampus, diencephalon, basal forebrain), language (Broca’s area and Wernicke’s area), visuospatial ability (the right side of: parietal lobe and frontal lobe), visual recognition (temporal and occipital lobes), executive function (parietal and dorsolateral prefrontal cortices, emotion-bundled-with-personality (temporolimbic system and orbitofrontal cortices), and resting state i.e., default mode network (medial temporal cortices, precuneus, anterior and posterior cingulate) involve a variety of brain circuitries, whose hierarchical ranks and regional positions might or might not always be adjacently and directly interconnected. The degree of success in this whole delivery strongly relies on the scaffolding power of gray matter that, as we know, already has so much bearing on the transmitting speed of white matter underneath. Yet, in most cases, especially, of brain abnormality—is unfortunately not always equally distributed across domains. Some domains could have either denser or thinner edges than another—relative to maturity, as well.

“For, in the first place, the brain is essentially a place of currents, which run in organized paths.”

—William James

Why doesn’t the emotional domain turn out well for the psychopathic brain? It is, therefore, more likely due to speed disruption at some nodes in this emotional net which then tethers to impact its synaptic-flow. That is, the temporolimbic system (the compounding temporolimbic here simply means limbic regions being part of the temporal lobe) and orbitofrontal cortices (OFC, also known for the frontier of sensory input located just behind the eye socket, which anatomically has direct connection with the brain’s fear center, amygdala). This salient white matter is also called uncinate fasciculus. Considering complex, at the granular levels, the fibers in each wire might or might not be so well-organized, depending on the value of the so-called fractional anisotropy (FA). To simplistically pick up on the idea, we can break it down to lexical components. So fraction here can be regarded as a disconnected piece, or in a word, fragment; whereas anisotropy technically means directionality dependent. And combine them together the fractional anisotropy can then be understood as the alignment rate. The lower is the FA value, the less organized and more disrupted are the UF fibers thus resulting poor alignment. Conversely, the higher is the FA value, the more organized and less disrupted are the UF fibers thereby resulting good alignment. So to know the network speed of white matter, it can be tested through the lens of fractional anisotropy measuring value from which its efficiency scale can also be predicted.

“It is a profound mistake to take the brain to be a solid mind.”

—John Hughlings Jackson

The marriage between language and personality vis-à-vis uncinate fasciculus is certainly no without debates and controversies. A few studies, however, have noteworthily emerged, irrespective of grey areas and considerably limited amount of research. Of whether there is a common thread between the white matter abnormality and the psychopathic criterion. One that in fact has once been conducted by Wolf et al (2015), involving adult inmates at a medium-security Wisconsin correctional facility using diffusion tensor magnetic resonance imaging (DT-MRI) to measure the diffusion rate of anisotropy in their salience network. They found there is reduced FA in the right UF. Specifically, they found this low rate to be associated with the interpersonal facets of psychopathy—glib, superficial charm, grandiose sense of self-worth, pathological lying, conning/manipulativeness—the subset of Factor 1. This finding sounds plausible given, as explained earlier, uncinate fasciculus are bundling fibers responsible for the reconciliation of the emotionally-laden, social information with semantic computation across differing domains. More so, it is believed that, as it is consistent throughout the majority of neuroanatomy literature, UF strands are rooted in the limbic system, wherein amygdala resides appears to be flat-out dysfunctional in psychopathy. This further translates to this idea that uncinate fasciculus could otherwise play critical role in social-affective function in addition to decision-making process as this pathway is routing bi-directionally to the anterior part of the temporal lobe and inferior part of the frontal lobe.

“Men use thought only to justify their wrong doings, and employ speech only to conceal their thoughts.”

—Voltaire

[sidebar] Abnormality (of any kind), to put it in a wonky analogy, can also look like when the differing departments and sub departments within a company no longer share the same goal and value as one entity. Therefore, a disorder within.

Finally, while the biological mechanisms underlying this reduced uncinate fasciculus remain unclear, one interesting paradox we can confidently pick up on this whole machinery of psychological surgery is this reality where ones need not to be emotional to work the emotions of others for whatever their ultimate ends in question. Some of them might be completely devoid of it after all, which psychopaths are indeed. Relates back to Cleckley’s observation with regard to the very latter:

“He can learn to use ordinary words, and even extraordinarily vivid and eloquent words…He will also learn to reproduce appropriately all the pantomime of feeling; but the feeling doesn’t pass.”

(The Mask of Sanity, p. 374)

References

Babiak, P., & Hare, R. D. (2006). Snakes in Suits: When Psychopaths Go to Work. Harper Business.

Baumeister, R. F. (1999). Evil: Inside Human Violence and Cruelty. Henry Holt and Company.

Blair, R. J. (2007). The amygdala and ventromedial prefrontal cortex in morality and psychopathy. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 387-392. DOI: 10.1016/j.tics.2007.07.003

Broomhall, L. (2005). Acquired Sociopathy: A Neuropsychological Study of Executive Dysfunction in Violent Offenders. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, 367-387. DOI: 10.1375/pplt.12.2.367

Cleckley, H. M. (1941). The Mask of Sanity: An Attempt to Clarify Some Issues About the So-Called Psychopathic Personality. Mockingbird Press LLC.

Craig, M., Catani, M., Deeley, Q., Latham, R., Daly, E., Kanaan, R., . . . Murphy, D. (2009). Altered connections on the road to psychopathy. Molecular Psychiatry, 946-953. DOI: 10.1038/mp.2009.40

Dick, A. S., & Tremblay, P. (2012). Beyond the arcuate fasciculus: consensus and controversy in the connectional anatomy of language. Brain, 3529-3550. DOI: 10.1093/brain/aws222

Dutton, K. (2012). The Wisdom of Psychopaths: What Saints, Spies, and Serial Killers Can Teach Us About Success. Scientific American.

Filley, C. M. (2012). The Behavioral Neurology of White Matter (second edition). Oxford University Press.

Grotheer, M., Kubota, E., & Grill-Spector, K. (2021). Establishing the functional relevancy of white matter connections in the visual system and beyond. Brain Structure and Function, 1347-1356. DOI: 10.1007/s00429-021-02423-4

Hare, R. D. (1993). Without Conscience: The Disturbing World of the Psychopaths Among Us. Guilford Publications, Inc.

Hecht, D. (2011). An inter-hemispheric imbalance in the psychopath's brain. Personality and Individual Differences, 3-10. DOI: 10.1016/j.paid.2011.02.032

Heide, R. J., Skipper, L. M., Klobusicky, E., & Olson, I. R. (2013). Dissecting the uncinate fasciculus: disorders, controversies and a hypothesis. Brain, 1692-1707. DOI: 10.1093/brain/awt094

Kiehl, K. A., Smith, A. M., Mendrek, A., Forster, B. B., Hare, R. D., & Liddle, P. F. (2004). Temporal lobe abnormalities in semantic processing by criminal psychopaths as revealed by functional magnetic resonance imaging. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging, 297-312. DOI: 10.1016/s0925-4927(03)00106-9

Mneimne, M., Powers, A. S., Walton, K. E., Kosson, D. S., Fonda, S., & Simonetti, J. (2010). Emotional valence and arousal effects on memory and hemispheric asymmetries. Brain and Cognition, 10-17. DOI: 10.1016/j.bandc.2010.05.011

Munneke, J., Hoppenbrouwers, S. S., Little, B., Kooiman, K., Burg, E. v., & Theeuwes, J. (2018). Comparing the response modulation hypothesis and the integrated emotions system theory: The role of top-down attention in psychopathy. Personality and Individual Differences, 134-139. DOI: 10.1016/j.paid.2017.10.019

Olson, I. R., Heide, R. J., Alm, K. H., & Vyas, G. (2015). Development of the uncinate fasciculus: Implications for theory and development disorders. Development Cognitive Neuroscience, 50-61. DOI: 10.1016/j.dcn.2015.06.003

Rutten, G.-J. (2017). The Broca-Wernicke Doctrine: A Historical and Clinical Perspective on Localization of Language Functions. Springer.

Schacter, E. A. (2006). Processing emotional pictures and words: Effects of valence and arousal. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neurosicience, 110-126. DOI: 10.3758/cabn.6.2.110

Smith, C. U., & Whitaker, H. (2014). Brain, Mind and Consciousness in the History of Neuroscience. Springer.

Voss, C., & Raz, T. (2016 ). Never Split the Difference: Negotiating as if Your Life Depended on It. Harper Business.

Wolf, R. C., Pujara, M. S., Motzkin, J. C., Newman, J. P., Kiehl, K. A., Decety, J., . . . Koenigs, a. M. (2015). Interpersonal Traits of Psychopathy Linked to Reduced Integrity of the Uncinate Fasciculus. Human Brain Mapping. DOI: 10.1002/hbm.22911

Yang, Y., Raine, A., Colletti, P. M., Toga, A. W., & Narr, K. L. (2009). Abnormal temporal and prefrontal cortical gray matter thinning in psychopaths. Molecular Psychiatry, 561-562. DOI: 10.1038/mp.2009.12

*The Narrative Convincer. This characterization is borrowed from the book The Confidence Game by Maria Konnikova